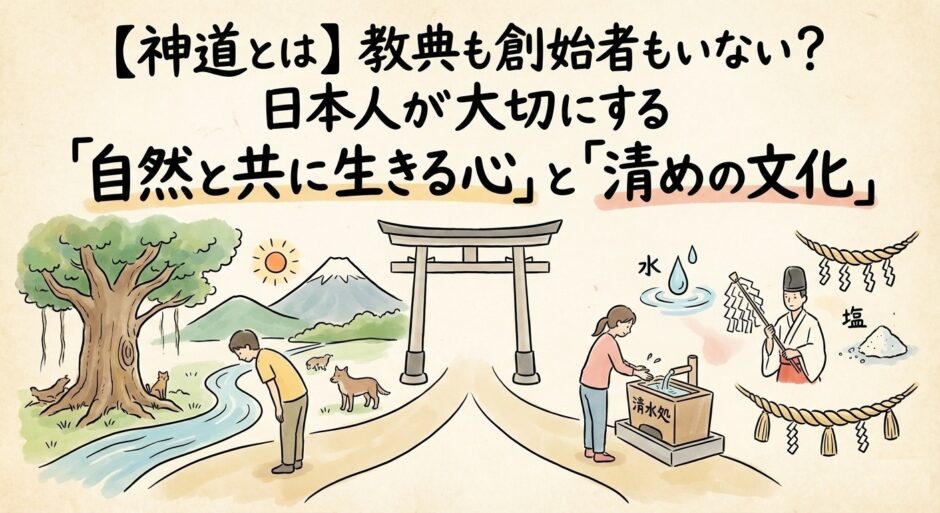

Have you ever stepped into a Japanese shrine and suddenly felt the air change? The rustling of trees, the sound of gravel underfoot, and an almost solemn stillness.

“Shinto” might actually be described less as a religion and more as the very essence of the sense of “reverence for nature” and the pursuit of ‘purity’ that we Japanese have cherished since ancient times. This time, rather than delving into complex doctrines, we’ll explain in simple terms the worldview of “Shinto” that lies at the heart of why the Japanese hold shrines so dear.

1. The Reason There Is Neither Founder Nor Scripture

Shinto has no sacred texts like the Christian Bible or the Islamic Quran. Nor does it have a founder like Jesus Christ or Buddha.

This is because Shinto is not a teaching created by anyone, but rather “customs that arose naturally from Japan’s environment.” In ancient times, people feared severe natural disasters while simultaneously giving thanks for the blessings of the sun and rain. “Great rocks,” “deep forests,” “thunder,” and “wind.” They called the very energy of nature, beyond human power, “kami,” and clasped their hands in reverence.

In other words, Shinto is not about “learning teachings,” but about “feeling the greatness of nature and giving thanks.”

2. “The Eight Million Gods”: Everything possesses a soul.

In Shinto, there is the phrase “Yaoyorozu no Kami” . It is translated as “8 million,” but this actually means “countless.”

- God of the Mountains

- God of the Sea

- God of the Toilet

- God of Rice

Not only living things, but also places and tools are believed to harbor spirits. The reason Japanese people use things carefully for a long time, or hold memorial services for worn-out needles and brushes (Needle Memorial Service, Brush Memorial Service), is because the Shinto spirit of gratitude toward objects, “okagesama,” is deeply rooted in them.

3. Why Wash at the Hand-Washing Basin? “Impurity” and “Purification”

The most important concept in Shinto is purity.

In Shinto, the state of having one’s spirit withered by sin, mistakes, illness, or misfortune is called “impurity” (kegare). (One theory suggests the origin lies in ‘ki’ withering = ki-kare). Washing away this impurity with water or rituals to restore one to a pure state (a healthy state) is called “purification” (harai).

Washing your hands and mouth at the temizuya (water ablution pavilion) before entering a shrine is not merely a matter of hygiene. It is a switch to shed the “impurity” acquired in the outside world and reset your mind. The feeling of “feeling refreshed” after visiting a shrine can be attributed to the effect of this “purification.”

4. Shinto Blending into Everyday Life

Many Japanese people say, “I am not religious,” but in fact, they practice Shinto in every aspect of their daily lives.

- “Itadakimasu”: Gratitude for receiving the life (divine spirit) of the ingredients.

- Festival: An event to honor the gods and deepen community bonds.

- First shrine visit, Shichi-Go-San, and first shrine visit for newborns: Customs to report life milestones to the gods.

- Groundbreaking ceremony: A ritual to greet the spirits of the land before building a house.

These are not so much religious obligations as they are feelings ingrained in the Japanese DNA—a sense that “it feels better to do so” or “it brings peace of mind.”

5. The Mysterious Connection with Buddhism

Japan also has many Buddhist temples. Globally, it is rare for different religions to blend together, but in Japan, Shinto and Buddhism have fused over a long period of time (Shinbutsu shūgō).

- Weddings at shrines (Shinto): Celebrating new bonds

- Funerals at temples (Buddhist): Praying for peace in the afterlife

This spirit of tolerance, which values both roles while dividing responsibilities, is a major characteristic of the Japanese mindset.

Manager’s Comments

When I take overseas friends to shrines, they sometimes ask, “Why do Japanese people pray to trees and rocks?” That’s when I answer like this: “It’s because we feel like this tree has been here for hundreds of years, watching over us like an elder.”

Shinto is less a “religion of belief” and more a “sensibility of feeling.” Forget complicated theories—just take a deep breath within the shrine grounds. I believe that very “sense of comfort” you feel there is the essence of Shinto.

Tour of Japanese shrines and temples

Tour of Japanese shrines and temples